Canada, despite breaking even in the War of 1812, was still envisioned to be an easy target for American expansion. The economies of the two sides had already become a bit invested in one another, especially in the realm of timber products. Much of the virgin forests of the eastern United States had already found their way into the focus of the growing cities, and Canadian timber interests found a ready market south of the border as well as to a far more distant England. A huge advantage existed in directing more trade to the United States, as transport of wood to Britain required wasteful squaring of trees in order to more efficiently fit into ship hulls. Sending wood to the United States by overland networks, railways, and even directly on rivers meant that more wood could be turned into cash, pound for pound. The authorities in Washington were well aware of how lucrative business was between the two parties, which was of great advantage in warming public relations between what had formerly been hostile enemies. If an invasion did happen, surely the Canadians would consider the economic benefits at stake if they decided to fend it off...

Furthermore, Canada was not really Canada, at least not as we know it. Oh, the word certainly existed, and people from Cape Breton to the trading outposts in the Ontario frontier called themselves Canadians when it suited them. Any sort of concept of a national mutual appreciation society was just so far away, however. Quebec planted its feet firmly in a defensive position against les Anglais. Ontario looked across the Ottawa River in disgust. Nova Scotia and the rest of the Atlantic front felt ignored by these two lands. British Columbia might have very well been considered to be on a different planet. Many of these situations have hardly become laughing matters assigned to the bin of history!

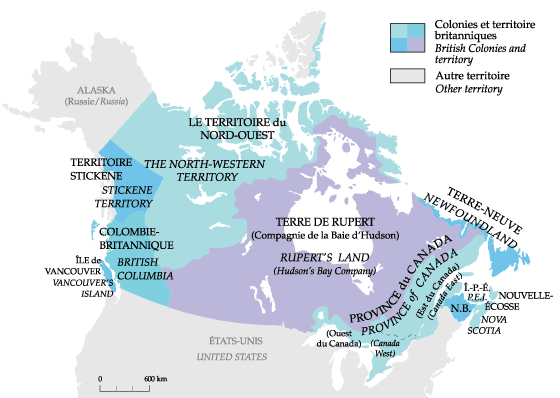

|

| Courtesy of Canadian Geographic, where you can find other excellent maps on Le Nord. |

The truth was, Canada would be easy to invade because it could be picked apart piece by piece, with the people of one area probably not even considering to help their neighbors. Or so the Americans thought...

Come by tomorrow for part three.

No comments:

Post a Comment